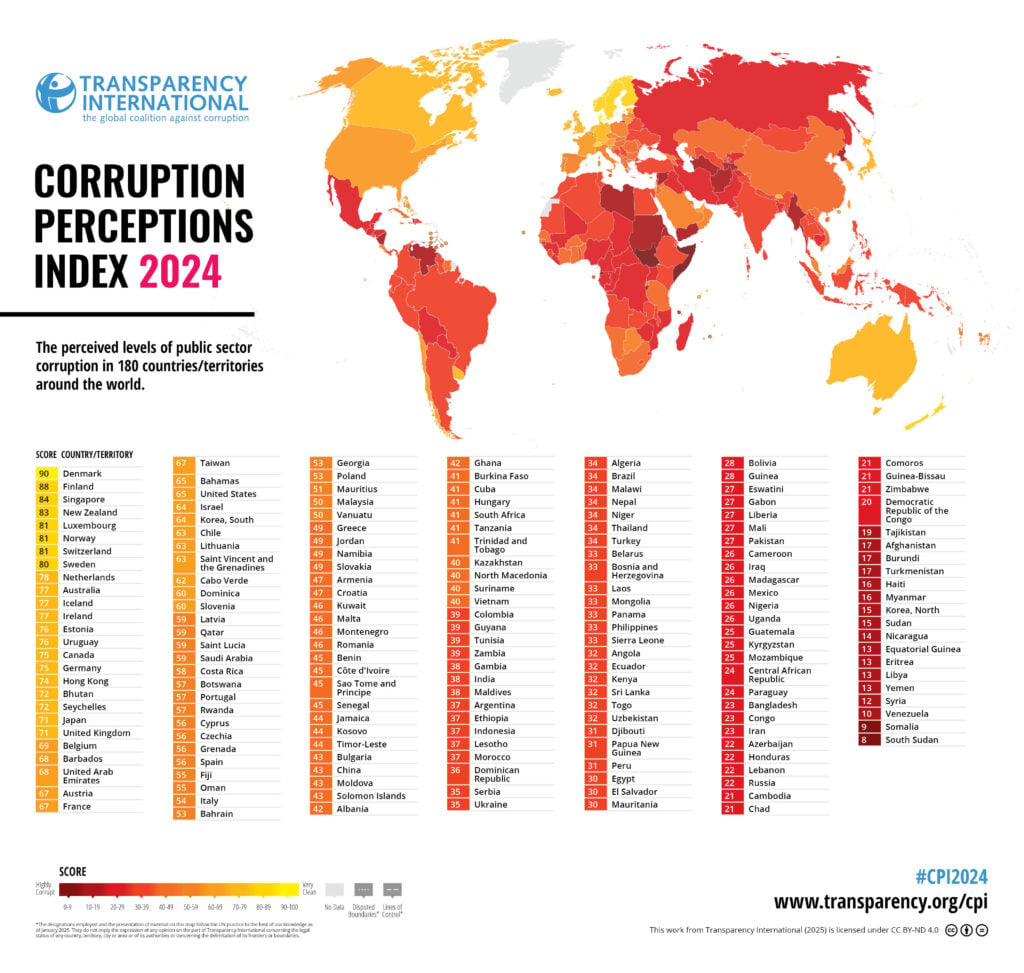

For the first time since 2010, Singapore has been ranked as the least corrupt country in the Asia-Pacific region, according to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) 2024 report released on 11 February.

The Republic also achieved its highest global ranking since 2020, placing third globally behind Denmark and Finland.

Singapore scored 84 out of 100, surpassing New Zealand, which had dominated the top regional spot for 14 consecutive years. This marks a significant improvement for Singapore, which ranked fifth globally in 2023.

The Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) attributed this success to the country’s long-standing zero-tolerance approach to corruption and its robust mechanisms for investigating misconduct, whether reports come from known or anonymous whistleblowers.

Globally, Denmark topped the index for the seventh consecutive year with a score of 90, followed by Finland at 88. New Zealand, which scored 83, and Luxembourg, with 81, rounded out the top five.

Despite Singapore’s rise, questions remain over the reliability of the CPI as a measure of actual corruption due to its perception-based methodology, which is susceptible to various biases.

Opaque transparency and limited media scrutiny

Unlike other high-ranking countries such as Denmark and Finland, which are known for strong press freedoms and public access to government information, Singapore’s anti-corruption reputation is built primarily on enforcement rather than transparency.

The country lacks comprehensive freedom of information laws, and its media environment has been described by international observers as tightly controlled.

This limited access to independent scrutiny and government data stands in contrast to the open reporting practices of nations like New Zealand and Denmark, which actively encourage public oversight.

Singapore is ranked 126th out of 180 countries in the 2024 Press Freedom Index and has been coloured black on the World Press Freedom Index map since 2020, indicating that the situation is classified as “very bad.”

Despite the “Switzerland of the East” label often used in government propaganda, the city-state falls only slightly short of China in terms of media suppression. In comparison, Denmark is ranked second, Finland holds the fifth position, and New Zealand is ranked 19th.

Singapore’s perceived cleanliness may, therefore, stem more from the public’s trust in the government’s enforcement mechanisms than from transparent governance.

Some commentators argue that this could lead to a situation where corruption cases are underreported or known only to internal bodies like the CPIB, making independent assessments challenging.

Transparency International has acknowledged that the CPI measures perceptions of corruption, not actual occurrences.

Factors such as media reports, high-profile cases, and whistleblower activity can influence these perceptions.

In highly controlled environments, the lack of publicly available scandals may be interpreted as an absence of corruption, even though it could also reflect restrictions on information flow.

High-profile cases test perceptions

One key development in 2024 that tested Singapore’s clean reputation was the conviction of former transport minister S. Iswaran, who received a 12-month jail sentence for corruption.

This marked the first time a former Cabinet minister had been jailed for such offences.

Although the case demonstrated the government’s willingness to hold officials accountable, critics suggest that such instances can paradoxically harm perceptions by highlighting corruption that might otherwise remain hidden.

A broader debate over the CPI’s methodology

The CPI report emphasised the importance of democratic institutions and free media in controlling corruption, noting that full democracies scored an average of 73 compared to just 33 for authoritarian regimes.

However, this raises concerns about countries like Singapore, which ranks highly despite its limited civic space.

Countries with stronger protections for press freedom, whistleblowers, and public access to information tend to have more robust mechanisms for uncovering and addressing corruption.

By contrast, nations where information is closely guarded may appear less corrupt simply because fewer cases are reported.

Despite its high ranking, Singapore faces challenges related to its financial and environmental oversight.

The report highlighted Singapore’s role as a transit hub for environmental crimes, with dirty money from activities like the illegal wildlife trade being laundered through its financial systems.

A risk assessment report in May 2024 acknowledged these vulnerabilities and the need for stricter monitoring.

As Transparency International noted, high rankings should not lead to complacency. “Even well-ranked nations can face significant corruption risks in sectors like finance, environmental protection, and procurement,” the report warned.

For Singapore, strengthening public oversight and press freedoms could help bridge the gap between its enforcement success and broader perceptions of government transparency.