Singapore’s current system of electoral boundary delineation gives the government “almost limitless discretion,” constitutional law expert Professor Kevin YL Tan warned during a public webinar held on 21 March 2025.

Hosted by AcademiaSG and chaired by media scholar Professor Cherian George, the hour-long session titled Fair and Foul drew over a hundred attendees.

Prof Tan used the platform to argue for deep reforms to Singapore’s electoral system, especially in light of the recent revisions to the electoral map announced on 11 March by the Electoral Boundaries Review Committee (EBRC).

The EBRC changes saw the number of elected Members of Parliament rise from 93 to 97. New constituencies were formed, others dissolved, and boundaries redrawn.

The government has attributed these adjustments to demographic shifts and population growth. However, critics, including Prof Tan, questioned the lack of transparency and accountability in the process.

Prof Tan asked, “Does Singapore’s current electoral system ensure fair representation?”

His answer was a resounding no.

He contended that electoral fairness is not merely about holding elections regularly but about the rules that govern the drawing of electoral maps and the distribution of political power.

“There is very, very little by way of law insofar as how we construct our electoral boundaries,” said Prof Tan.

He noted that the Constitution does not set out how many constituencies should exist, nor does it stipulate any criteria for how boundaries should be drawn. The power to determine electoral boundaries rests entirely with the Prime Minister, who appoints the EBRC.

Quoting a key judicial precedent, Prof Tan emphasised that “the notion of a subjective or unfettered discretion is contrary to the rule of law.”

He added, “All power has legal limits. The rule of law demands that the courts should be able to examine the exercise of discretionary power.”

In his analysis, Prof Tan reviewed Singapore’s constitutional history, noting that until 1984, the number of constituencies was embedded in the Constitution.

After that year, the responsibility was shifted to ordinary legislation under the Parliamentary Elections Act. Section 8 of the Act, he explained, gives the minister the authority to “specify the names and boundaries of the electoral divisions” via gazette notification—without requiring parliamentary debate or approval.

He also highlighted the effects of this centralised power on the electoral map, offering personal anecdotes to illustrate the volatility of boundary changes.

“I lived in the same house in Bedok for 18 years. First it was Bedok SMC, then Eunos GRC, then Aljunied GRC—without me ever moving,” he said.

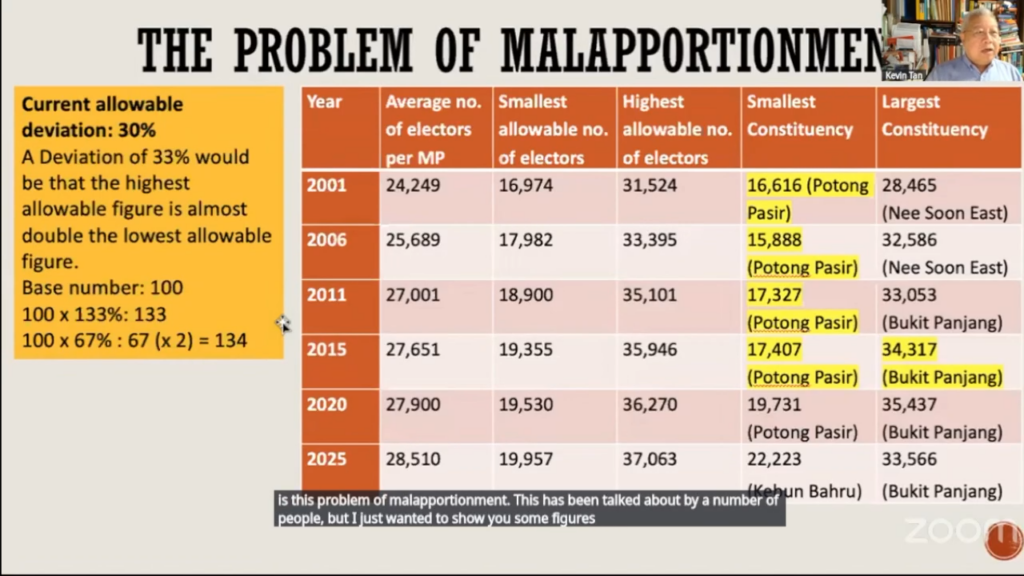

Prof Tan accused the current system of fostering malapportionment.

Using government data, he showed that the size of electorates in different constituencies could vary by nearly 100%, resulting in votes in some areas being worth far more than others.

“A voter in Potong Pasir has almost twice the voting power of someone in Bukit Panjang,” he noted.

He attributed this imbalance to an official deviation allowance of up to 30% from the national average voter population per MP, a threshold introduced in 1980. He questioned the rationale behind it, especially in a developed city-state with relatively stable urban populations.

“This is not Malaysia in the 1960s. We don’t have rural hinterlands where population densities vary wildly. Singapore is highly urbanised. The 30% deviation is too high,” he argued.

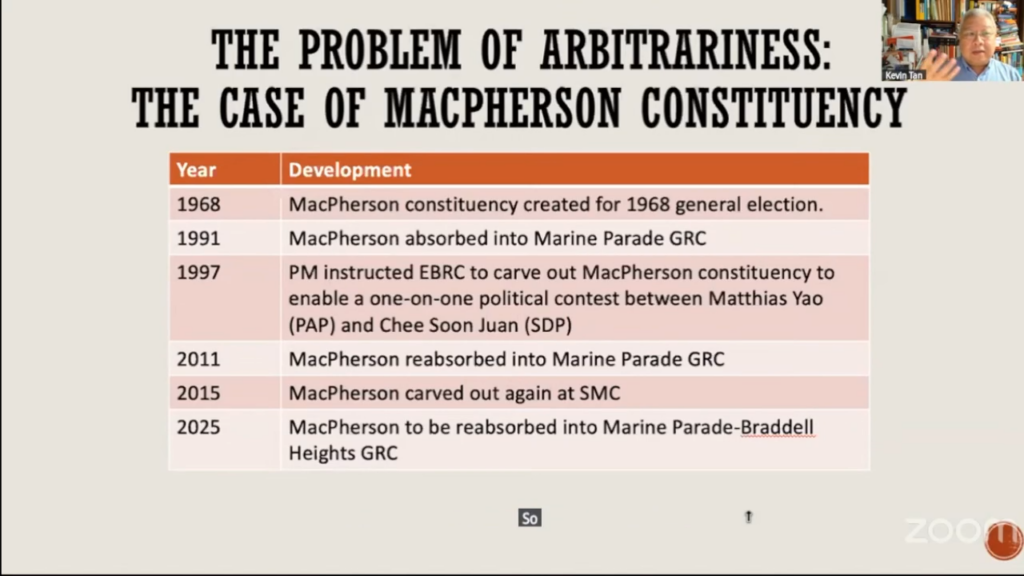

Prof Tan also presented historical examples where constituencies that favoured the opposition were either dissolved or absorbed into larger GRCs.

He cited the case of MacPherson SMC, which was alternately created and dissolved across elections. “It makes nonsense of the delineation process,” he remarked.

Prof Tan recounted how MacPherson, first created in 1968, was absorbed into Marine Parade GRC in 1991, only to be carved out again in 1997 for what appeared to be a political purpose: to facilitate a direct contest between opposition politician Dr Chee Soon Juan and then-PAP candidate Matthias Yao.

“This was a one-on-one fight—Chee had challenged Yao to step out from behind the GRC system. And the government effectively redrew the map to make it happen,” Prof Tan said.

After that contest, MacPherson was reabsorbed into Marine Parade GRC in 2011, then carved out again as an SMC in 2015. In the most recent boundary changes, announced on 11 March 2025, MacPherson has once again been dissolved and folded into the newly created Marine Parade Heights GRC.

Prof Tan highlighted that such boundary volatility had occurred despite residents never moving. “You can live in the same home for 30 years and find yourself in four or five different constituencies,” he said, adding that this undermines both democratic clarity and political accountability.

He raised concerns over the decentralised vote-counting system introduced in 1997. The change allowed vote tallies to be broken down by precinct, providing parties with detailed insights into voting behaviour.

While this does not breach ballot secrecy, Prof Tan argued it created opportunities for gerrymandering. “The party contesting every seat—the PAP—is the only one with complete data,” he said.

When asked whether elections in Singapore were “free but not fair,” Prof Tan responded cautiously but firmly.

He praised the Elections Department’s competence in administering polls and safeguarding ballot secrecy but maintained that the process of drawing electoral boundaries is fundamentally flawed.

As a solution, he proposed the following reforms:

- Creation of an independent elections commission with constitutional protection and oversight over boundary delineation.

- Codified guidelines for how boundaries are drawn, with emphasis on numerical equality, geographic coherence, and community identity.

- A minimum one-year buffer between the announcement of new boundaries and the next general election.

- Prohibition on the use of precinct-level results in the boundary-drawing process.

- Provision for appeals against illogical or impractical boundary maps.

“This is not rocket science,” he said, pointing to the example of the 1959 All-Party Delimitation Committee, which operated under principles such as equal vote weight, community cohesion, and geographical clarity.

“These were common-sense values then, and they should be now.”

In response to a question on international models, Prof Tan noted that many democracies either have fully independent commissions or multiparty committees with judicial oversight.

“Most of them operate with tighter population variances—around 15%,” he said, comparing this to Singapore’s 30%.

When asked whether such reform could happen without political will from the ruling party, he acknowledged the challenge but insisted that public pressure and informed discussion were essential.

“We need to keep raising awareness,” he said. “A fair electoral system benefits everyone, regardless of who is in power.”

The session ended with a reflection from host Prof Cherian George, who noted: “It’s clear that while the system is technically efficient, it needs to be fundamentally fair. That’s the essence of democratic integrity.”

The post Prof Kevin YL Tan calls for independent elections commission to address electoral fairness in Singapore appeared first on The Online Citizen.