SINGAPORE: Ho Ching has again sparked public debate, this time by defending the record-high S$52,188 monthly rent awarded to a general practitioner (GP) clinic in Tampines.

In a Facebook post published on 5 June 2025, Ho, the former Chief Executive of Temasek Holdings and spouse of former Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, justified the bid by arguing that the clinic’s operators had conducted due diligence and would not pass high rental costs directly to patients.

Her position stands in contrast to Health Minister Ong Ye Kung, who had earlier described the bid as “dismaying” and cautioned that such steep rental rates would ultimately raise healthcare costs.

Ho’s case for value-driven high rent bids

Ho argued that a higher rental price could support improved services, such as extended operating hours, multi-doctor practices, and possibly 24/7 urgent care clinics.

“These could be excellent partners for a healthier SG in preventive and chronic care,” she wrote, suggesting that higher overheads push clinics to innovate and maximise value.

Referring to public reactions over the rental figure, Ho cautioned against overreaction: “Let’s not go hijjies-bijjies when we see large topline numbers.”

She underscored that from a patient’s point of view, a high rental does not automatically mean higher consultation costs.

Ho’s defence focused on the winning bidder, I-Health, a medical group that already operates three clinics.

She highlighted that I-Health had prior experience bidding for Housing and Development Board (HDB) clinic sites and knew the operational costs involved.

Citing news reports, Ho pointed out that the clinic plans to break even within 18 months, offering extended hours, hiring more doctors, and treating 100–150 patients daily.

“This means this is not a small clinic, but one which can accommodate at least two doctors at any one time,” she noted.

At 100 patients per day and S$33 per consultation, the topline revenue would reach S$99,000 monthly—excluding revenue from additional services such as medication, according to Ho’s estimation.

Ho backs open tender policy and warning against rent control

Ho criticised suggestions of rent control, warning that such measures could suppress innovation and entrench complacency.

She argued that artificial caps tend to benefit incumbents and restrict competition.

“The race to the bottom means poorer outcomes in the longer run, and a less robust market,” she wrote.

To explain bidding dynamics, she referred to second-price auction models—where the winning bidder pays the price of the second-highest bid—as a way to prevent the “winner’s curse”.

This model, she said, allows the market to remain open and competitive while avoiding unsustainable bids.

She also described an alternative model involving a low base rent with revenue sharing, which enables new businesses to start with reduced risk.

However, she warned that successful tenants who had opted for such schemes should not later complain about sharing upside profits.

Invoking the Chinese idiom 饮水思源 (“when you drink water, remember its source”), Ho called on businesses to recognise the early support they received.

MOH’s new tender framework in response to high rents

In response to concerns about rising rents, the Ministry of Health (MOH) and HDB introduced a new tender framework in May 2025.

Known as the Price-Quality Method (PQM), the framework gives 70% weight to healthcare quality factors and only 30% to the rental price.

Evaluation criteria include proposed care models, staffing, clinic hours, and expected community impact.

The PQM model was piloted at Bartley Beacon, where a 100 square metre clinic unit was tendered under the revised rules.

Public reactions divided over rent and access

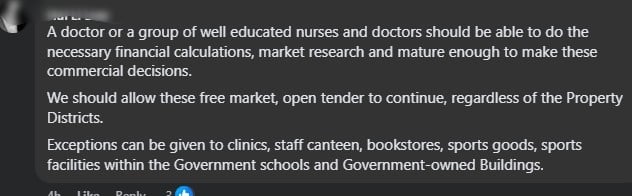

Ho’s post has drawn mixed reactions online, with some netizens agreeing with her free-market stance.

They argue that mature medical operators are capable of assessing financial risks and making commercial decisions.

These users believe the open tender system should continue, with exceptions only for specific facilities such as school canteens and government-owned premises.

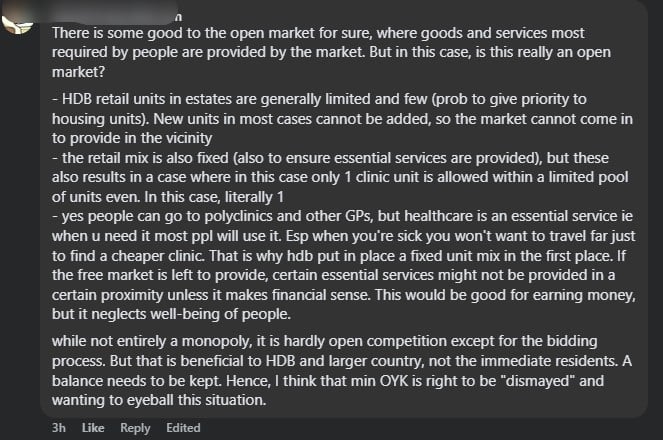

However, many others side with Minister Ong, stating that the clinic space market in HDB estates is not truly open due to fixed retail compositions and limited supply.

These constraints, they argue, create localised monopolies and restrict residents’ access to affordable healthcare.

Some also criticised the current model for benefiting landlords while neglecting community well-being.

Affordability and service quality under scrutiny

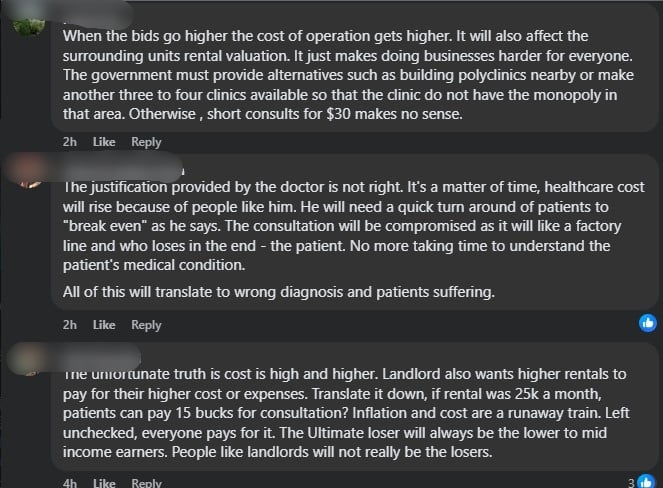

Netizens also expressed scepticism about Ho’s claims of cost containment.

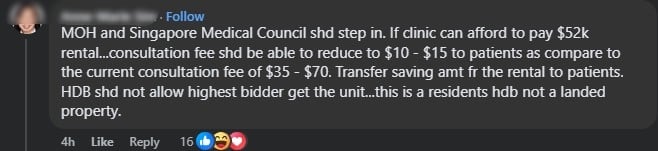

Some cited personal experiences with GP consultation fees reaching as high as S$80 and called for oversight from the MOH or Singapore Medical Council (SMC).

They argued that if a clinic pays over S$50,000 in rent, it should either be barred from passing the cost on to patients or be prevented from placing such bids altogether.

Concerns were also raised about service quality.

Users warned that clinics under financial pressure might shorten consultations to meet patient volume targets, increasing the risk of misdiagnosis and reduced care standards.

Another point of concern was the inflationary impact of such high bids on the surrounding retail ecosystem.

Some noted that record-high clinic rents could drive up valuations of adjacent units, indirectly raising operational costs for all businesses in the area.

Calls for systemic solutions to balance cost and care

To avoid such scenarios, some commentators proposed expanding the number of clinic sites or building more polyclinics in underserved areas.

This, they argued, would dilute the pricing pressure caused by scarcity and improve healthcare access for lower- and middle-income residents.

They cautioned that if the current trend continued unchecked, it would benefit landlords and investors at the expense of residents’ well-being.

The post Ho Ching disagrees with Ong Ye Kung, defends S$52k Tampines clinic bid and warns against rent control appeared first on The Online Citizen.