On 16 September 1963, Singapore gained independence from British colonial rule by joining the newly formed Federation of Malaysia — alongside Malaya, Sabah, and Sarawak — ending more than a century of British governance and launching a new regional federation.

It was the culmination of years of negotiation and political manoeuvring, and for Singapore, a critical step toward self-governance within a sovereign alliance.

Though this moment marked the formal end of colonial rule, it has been largely overshadowed in Singapore’s public memory by its later separation from Malaysia on 9 August 1965 — the date now celebrated as National Day.

In contemporary Singapore, 16 September passes largely unacknowledged.

Historian Thum Ping Tjin, in his annual Facebook post marking the day, has consistently questioned why the country does not officially recognise the date as its moment of independence.

In his latest post, he described 16 September as “arguably the most significant day in our modern history” and called for greater reflection on its absence from the national calendar.

How Singapore and Malaysia left colonial rule in 1963

By the early 1960s, both Singapore and Malaya viewed merger as a necessary step in completing the decolonisation process.

For Singapore, full independence was politically out of reach without British consent. The British colonial authorities were reluctant to grant sovereignty to a small island state with a volatile political climate and a strong leftist presence.

A merger with a larger, anti-communist Malaya aligned Singapore with British geopolitical interests, while offering an indirect route to independence.

For Malaya, absorbing Singapore was a matter of regional stability. Leaders in Kuala Lumpur, including then Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman, were concerned that Singapore — with its large Chinese population and active labour movement — might become a base for communist influence just across the causeway.

Bringing Singapore into the federation allowed Malaysia to tighten security control and manage cross-border political dynamics.

Thus, the formation of Malaysia on 16 September 1963 was seen as mutually beneficial — a solution that aligned political interests, economic needs, and colonial expectations.

A referendum paved the way to merger

In 1961, then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew proposed merger with Malaya as a route to independence and economic security. But the idea faced significant domestic resistance, particularly from the left-wing opposition, Barisan Sosialis, who saw the terms as unfavourable to Singaporeans.

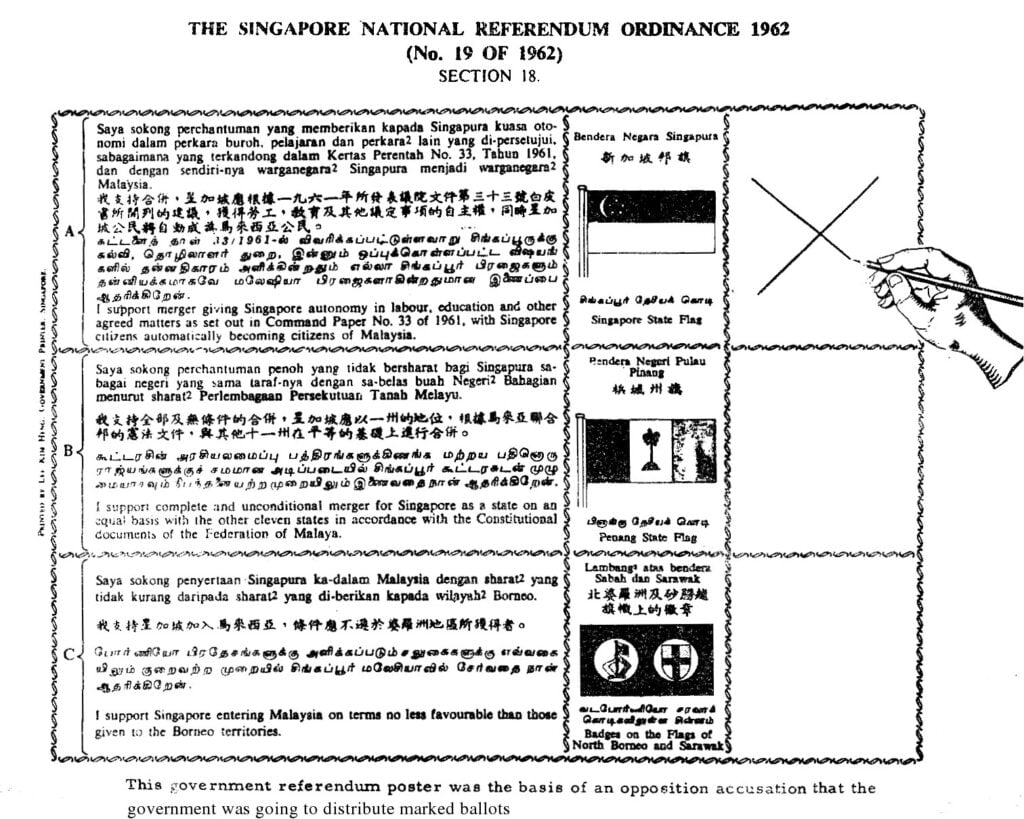

To legitimise the move, the PAP government held a popular referendum on 1 September 1962 — the first and only national referendum in Singapore’s history — offering voters three options, all involving some form of merger. A “no merger” choice was not included.

The three options were:

- Merger on the PAP’s terms, outlined in a government White Paper;

- Full and unconditional merger on equal state terms;

- Merger with terms equal to those of the Borneo territories.

The PAP’s preferred model — which retained control over education and labour, while ceding defence and foreign affairs to Kuala Lumpur — received 71% of the vote.

Critics described this as a Hobson’s choice — all three options led to the same outcome: integration with Malaysia, with no alternative presented.

Nonetheless, the result gave the appearance of public consent, and paved the way for Singapore’s formal entry into Malaysia on 16 September 1963.

Tensions emerged quickly within the federation

The merger was conceived as a partnership of equals, but political tensions soon surfaced. The PAP and Malaysia’s ruling United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) had divergent visions for the new nation.

UMNO promoted Malay political primacy under the framework of Bumiputera policies. The PAP, by contrast, campaigned for a “Malaysian Malaysia” — advocating equality across all ethnic groups.

This ideological rift widened when the PAP decided to contest in the 1964 Malaysian general election, winning only one of the 11 seats it contested. The move was seen by UMNO as a breach of trust and a direct challenge to its political dominance.

The situation escalated into public clashes and racial tensions, culminating in Singapore’s expulsion from the federation.

A pragmatic end to an uneasy union

On 9 August 1965, Singapore became an independent republic — but only after having already been a sovereign state for nearly two years under the Malaysia Agreement.

The separation allowed both governments to move forward independently. For Malaysia, it defused political discord.

For Singapore, it offered full control over its own finances, domestic policy, and international relations.

Each nation pursued its own developmental trajectory, but their shared starting point — the 1963 merger — remains a key legal and historical foundation.

Why the merger is overlooked in official memory

Singapore’s path to independence was neither abrupt nor wholly self-determined. The British colonial authorities were unwilling to grant full sovereignty to Singapore in the early 1960s, largely due to the island’s volatile political climate, active labour movement, and strong left-wing presence.

Merger offered a politically acceptable way forward. By integrating with a larger, anti-communist and Commonwealth-aligned federation, Singapore gained independence under conditions deemed secure by both London and Kuala Lumpur.

The formation of Malaysia on 16 September 1963 therefore marked Singapore’s legal independence from British rule — an internationally recognised act of decolonisation, achieved through negotiation and strategic alignment.

By the time of its separation in August 1965, Singapore was already a sovereign entity. The proclamation of independence that year was a constitutional break from Malaysia, not the original act of decolonisation.

However, acknowledging 16 September as Singapore’s true independence day would require confronting several uncomfortable truths about that period:

- That independence was attained through British and Malaysian approval, not solely on Singapore’s terms.

- That left-wing opposition, including figures like Lim Chin Siong, opposed the merger — and many were detained without trial under the Internal Security Act during Operation Coldstore, weakening electoral resistance and altering Singapore’s political landscape.

- That these detentions — carried out in the name of national security — were instrumental in securing the PAP’s political dominance for decades to come.

This history remains contested, particularly because of how it is remembered — or omitted — in official accounts.

In 2014, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, writing about the Battle for Merger exhibition, repeated the claim that Barisan Sosialis was “communist-controlled,” citing handwritten documents allegedly linking Lim Chin Siong to underground communist activity.

Historians have challenged this narrative. Dr Thum Ping Tjin and others have called for the declassification of internal security documents, arguing that publicly available British records suggest Lim operated independently of any foreign directive.

A 1962 diplomatic report by British official Philip Moore concluded:

“While we accept Lim Chin Siong is a Communist, there is no evidence that he is receiving his orders from the MCP, Peking or Moscow.”

Moore added that Lim’s primary objective appeared to be gaining constitutional power in Singapore — not the establishment of a communist state.

Such assessments run counter to official portrayals that equated leftist nationalism with subversion.

This conflation has shaped the national narrative, contributing to the erasure of 16 September as Singapore’s first legal independence — and the sidelining of those who resisted the terms under which it was achieved.

Official silence and diplomatic contrast

Despite the legal and historical importance of 16 September 1963, Singapore does not mark the day in any official capacity. There is no public commemoration, media coverage, or acknowledgment of its role as Singapore’s first independence day.

In contrast, Malaysia celebrates Malaysia Day each year with official ceremonies and national reflection — recognising the federation’s founding.

This silence sits awkwardly alongside Singapore’s contemporary diplomatic rhetoric.

At the 11th Malaysia–Singapore Leaders’ Retreat, held on 7 January 2025, Singapore Prime Minister Lawrence Wong reaffirmed strong bilateral ties, saying:

“We have built up a very strong understanding friendship, a relationship built on trust… we are celebrating our shared heritage.”

Wong cited cultural exchanges and upcoming celebrations marking 60 years of diplomatic relations — calculated from 1965, not 1963.

Yet, the date of their first political union — 16 September — passed without mention.

This dissonance is striking.

Despite speaking of shared futures and intertwined histories, Singapore continues to behave as though Malaysia Day — and the merger that granted its independence — is someone else’s story.

The post Reflecting on 16 September: The day Singapore and Malaysia stepped out of colonial rule appeared first on The Online Citizen.